Rethinking Agriculture and Transportation Infrastructure in a Climate Changed U.S.

Engineering.com September 13, 2019This an excerpt from the full article. Read the full article here.

Replacing Fertilizers

The existing industrial agricultural system relies on fossil fuels in various ways and has destructive impacts on the global ecosystem, including the maintenance of the stable climate we’re accustomed to in the current Holocene era.

Nitrogen fertilizers are the result of ammonia created from the removal of hydrogen from natural gas. About 100 megatons of nitrogen fertilizer were used on the planet in 2010, compared to just three in the 1950s. Phosphorous and potassium fertilizers may not be derived from fossil fuels, but they are mined, which requires considerable energy.

This year, we learned that methane, a greenhouse gas roughly 30 times more potent in the near-term than carbon dioxide, from fertilizer production is 100 times greater than what companies are reporting. Additionally, fertilizer flows from fields to our waterways, creating algae blooms and dead zones in the ocean.

According to Mitchell, these issues and more could be addressed by abandoning chemical fertilizers.

“Several organizations around the world have determined that we could sequester as much carbon from the atmosphere as we’re currently emitting each year if we shifted to 100 percent regenerative agricultural practices,” he said.

Regenerative agricultural practices include the following, among others:

- Replacing fertilizer with compost

- Implementing no-till agriculture

- Abandoning herbicides

- Regular crop rotation

- Replacing monoculture crops with polyculture planting

- Holistically managed grazing

The point of regenerative agriculture is to think of crop production as a holistic process that considers the larger ecosystem, deploys techniques that actually restore topsoil, increases biodiversity, improves the water cycle and even sequesters carbon—all aspects of the ecosystem that have been greatly degraded by industrial farming.

“One thing that people don’t quite realize is that the amount of carbon weight in an old-growth forest above the surface of the earth is approximately equal to the weight of carbon that is being stored in the microbiome fungus beneath the forest that is being fed by the tress in a symbiotic relationship between tree and fungus,” Mitchell explained. “The fungus gets minerals and supports the trees, storing carbon in the form of sugars in the soil that way. The use of glyphosate [the primary ingredient in RoundUp and other herbicides] necessarily destroys these microbiomes. It kills off the fungus beneath the surface of the earth, so you don’t have that flow of carbon to the soil.”

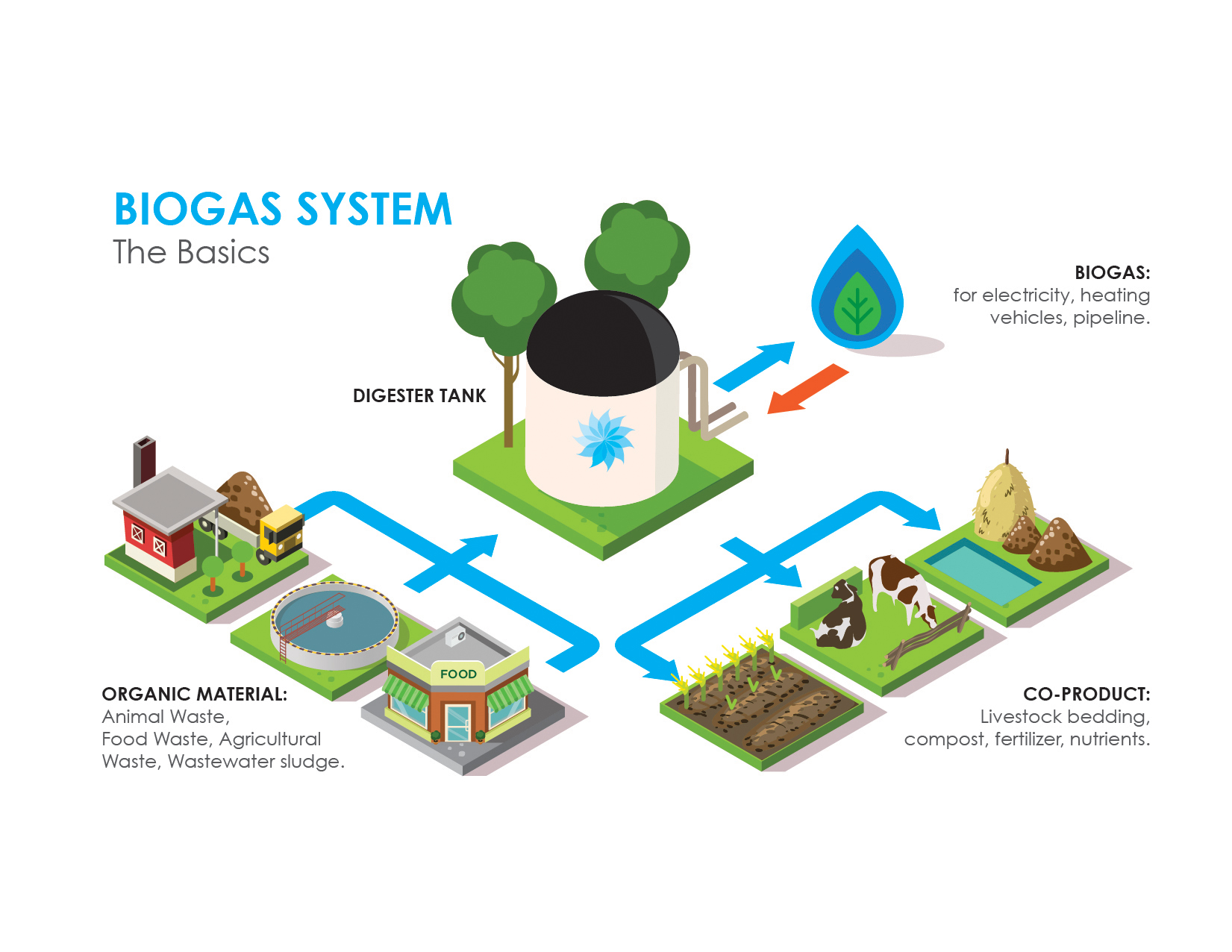

The state of Connecticut has been moving in the right direction, according to Mitchell. The state performs food waste collection, which can then be used both for the generation of biogas and the creation of compost. In some parts of Connecticut, companies like BlueEarth collect food scraps and deliver the resulting compost back to customers three times a year.

The actual composting is performed by firms like Quantum Biopower, which places the food waste in an industrial anaerobic digesting facility. During decomposition, the waste gives off methane, which is collected and burned in the same way that natural gas is. However, the food has already participated in sequestering carbon dioxide from the atmosphere that was emitted within the lifespan of the crops. For this reason, biogas is said to be carbon neutral.

Municipal composting also opens an opportunity for producing biochar, a carbon-rich type of charcoal made from heating organic biomass (such as food and agricultural waste) in an oven with little to no oxygen present, a process known as pyrolysis. Biochar is thought to have soil-enriching and water-retention benefits and, therefore, could be important for soil regeneration.

Compost and biochar production can be compatible operations due to the fact that feedstocks for compositing (biomass with high moisture, low lignin content) aren’t always ideal for biochar (low moisture and high lignin content) and vice versa. Moreover, biochar could play an important role in carbon sequestration.

“Combining compost, and anaerobic digestion with biochar work together for high efficacy amendments, that re regionally sourced and carbon negative,” Mitchell said.“Biochar production and anaerobic digestion facilities actually generate and sell electricity as an added bonus.”

Read the full article here.